Gary Foley reflects on the 1971 Springbok tour protests

In 1971, the all-white South African rugby team, the Springboks, toured Australia. The six-week-long tour was met with a boycott campaign involving rolling protests, strikes and constant disruption. Thousands of people joined in what became an important step forward for the international campaign against apartheid and a pivotal moment in the struggle for Aboriginal rights in Australia.

In 1971, Gary Foley was living in Redfern, Sydney. He was one of a number of radical Aboriginal activists, known as the Redfern Black caucus or the Black Power movement, who were forging a new chapter in the history of Aboriginal resistance. These activists wanted to fight the state and change the world. They were militant and daring and were fast becoming connected with the left and the trade union movement. Gary and other Black Power leaders became some of the key figures in the campaign against the Springboks. He sat down with me to talk about the protests, 50 years on.

We start by talking about why the apartheid system provoked protests in Australia. “In much the same way that the global discussion about racism going on today was set off by events in America, the touchstone in the ’70s was the white racist regime in South Africa”, says Foley. “It was the big global issue to do with racism at the time and an international anti-apartheid campaign had been growing since the Sharpevillle massacre in 1960.

“The issue came to a head in Australia because the then Liberal government decided that the Springboks would be allowed to play in Australia. This was despite sporting ties with South Africa having been cut by many other countries and a significant part of the British Commonwealth at the time. Australia was determinedly resistant to the campaign to boycott South Africa.”

South African sporting tours had become a polarising issue internationally—cheered on by racists and reviled by anti-racists. The Liberal prime minister at the time, Billy MacMahon, was keen to show support for South Africa because, as Gary puts it, “Two of the biggest racist countries, they stick together. Don’t forget the apartheid system was consciously modelled on the Aboriginal Protection Act of 50 years earlier ... and, of course, support for South Africa was necessary to stop the supposed spread of communism and terrorism”.

At the same time that apartheid was becoming a focus, a range of other issues were radicalising young people, making the mood ripe for a militant campaign. “Vietnam was huge for everyone at the time. It demonstrated the racist, imperialist system we were up against”, says Gary. There were many reasons for Aboriginal people in particular to be opposed to the Vietnam War. As Gary explains, “We had started to pay attention to the radical Black literature, the radical Black politics that was coming out of the US. And apart from recognising that the Vietnamese were another group waging a struggle against colonialism, we agreed with what Muhammad Ali had said about the Vietcong: that ‘no Vietcong ever called me nigger’”.

The anti-Vietnam War movement was personal for many in Australia, especially young people. Australia sent substantial numbers of troops and introduced conscription. Gary was tipped off by fellow activist Paul Coe that Aboriginal people did not have to serve in the military. “So I sent in a letter asking for an exemption. But the horrible thing was basically no other Black people knew you could do this, so they signed them up and sent them to war ... two of my cousins had to serve in Vietnam, and they came back, as everyone else did, completely fucked up.”

Aboriginal activists like Gary made links with the student left through the anti-war movement, and became connected with left-wing trade unions and unionists through it. “You know we had really strong ties in Redfern with Jack Mundey’s Builders’ Labourers [Federation] up there, Bobby Pringle and Joey Owens, they were the fucking legends. Bobby Pringle got arrested with me on three occasions, once at the Redfern tent embassy, and twice fighting coppers in Redfern at the Empress Hotel. I mean, these were trade union officials who were prepared to put their bodies on the line in accordance with their principles; you don’t see too much of that these days.”

Despite the radical atmosphere at the time, Gary still recalls being surprised that “Almost immediately when it was announced that the tour would go ahead, out of nowhere—well at least that’s the way it appeared to me at the time—an anti-apartheid movement materialised. Suddenly there were thousands of white Australians out there demonstrating against apartheid”. He pauses and then adds, “Well, it was a surprise on one level but, maybe not so dramatic if you take into account that this was only three years or so since 90 percent of the population voted ‘yes’ in the 1967 referendum”. The “yes” vote was for rewording references to Aboriginal people in the constitution, in a ballot overwhelmingly seen as a referendum on racism. “This had indicated to us that there was a reservoir of good will but, much like today, this was largely emotive. The anti-apartheid campaign helped to turn this into active support.”

In the weeks before the Springboks arrived, the demonstrations against the tour were growing and public opposition was building. By the time they touched down in Perth, they had a major problem. “The ACTU had slapped a black ban on them, ironically, a black ban. And it held.” With the pilots, liquor and hotel workers unions on board, “They couldn’t get anyone to fly them anywhere, or serve them anything or rely on anywhere to stay”.

Gary is quick to point out that this wasn’t to do with Bob Hawke, then ACTU president and later Labor prime minister. “If it was left up to him as an individual, they would have walked right in. It was because of the key unions with clout and the principled trade union officials that Hawke was brought over.”

This hostile situation meant that the government and the rugby associations went to extreme lengths to keep the Springboks’ whereabouts secret, especially in Sydney, where the movement was strongest. But they didn’t always succeed. As Gary recalls, “The Redfern Black caucus had relocated from Redfern at the beginning of 1971 due to police harassment. We secretly shifted our headquarters to a double storey old house in Bondi Junction. Next door was a big carpark and on the other side of the road from this carpark was a motel called the Squire Inn. One night we came home and saw all these police everywhere and buses pulling up. We realised the next morning that this was the ‘super secret’ location the Springboks were staying at. And so we opened up our commune to the anti-apartheid mob and made them cups of tea and stuff while they held an almost permanent protest in the carpark outside the inn. We had lots of good rallies there, making as much noise as possible to keep them awake at all hours”.

As fortuitous as this was, the centrality of the Redfern Black caucus was, of course, more than incidental. All over the country, Aboriginal radicals played a key role in the protests. One particularly colourful incident involved Jim Boyce, a former Australian rugby player who had been to South Africa as part of an Australian tour and had become a prominent member of the moderate wing of the anti-apartheid movement, approaching Gary and the other Black Power activists with a proposal. “He had three genuine Springbok rugby jerseys, from the ritual at the end of every game—you know they swap jerseys and all that—and he said to us: ‘The Prime Minister of South Africa has said no Black man will ever wear this particular jersey. If you guys were to put these on and turn up at a demo it would make headlines in South Africa’. And so we did.

“Me and Billy Craigie grabbed a jersey each and we walked across the carpark and stood in front of the Squire Inn. We were caught by surprise by a bunch of plain-clothes NSW special branch guys: they come running out of the hotel and they grab us, and then they haul us into the hotel and started at us with “Where did you steal these? Who did you steal these from?’ They called down the entire Springbok team to look us up and down; one by one they walked past us. These big, angry racist rugby players looked like they wanted to murder us. And they probably would have if the coppers hadn’t been around.”

Audacious stunts like these helped raise the profile of Black Power activists and drew attention to the issue of anti-Aboriginal racism. In Brisbane, which was another centre for the movement, activists Kath Walker and Denis Walker “provocatively dined with poet Judith Wright at the Springboks’ Brisbane hotel”.

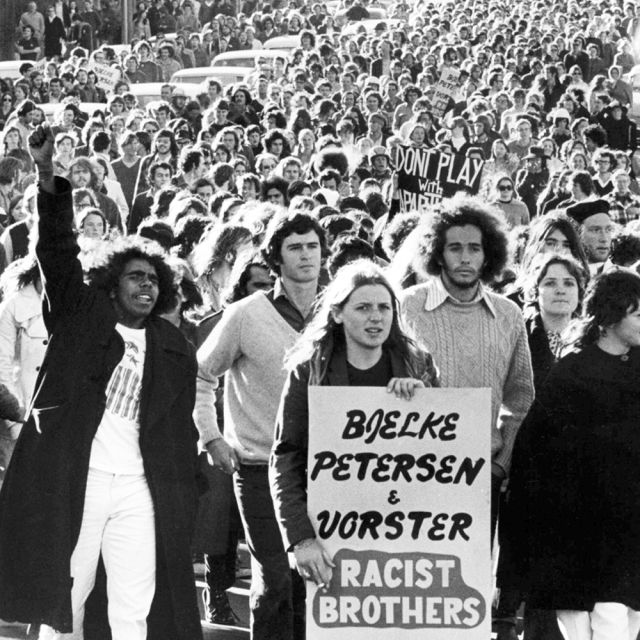

The audacity was not limited, however, to Aboriginal activists. Trade union activist John Phillips and Builders’ Labourers Federation president Bob Pringle walked into a sports ground in Paddington where the Springboks were due to play, and attempted to saw down the goal post. Leading anti-apartheid activists Verity and Meredith Burgmann posed as Afrikaans rugby goers and managed to invade the pitch at a high-profile game in Sydney. In Melbourne, one of the matches descended into a riot, with 200 protesters arrested. In Brisbane, a bitter fight took place. The authoritarian premier, Jo Bjelke-Petersen declared a state of emergency in order to protect the South African rugby entourage, and after protesters were brutalised at Tower Hill, a general strike was called. Across the country there were mass student meetings and mass demonstrations, with regular arrests.

The boycott campaign in Australia went further than similar campaigns in other countries. In particular, the union activity took things to a new level. Nowhere else had union bans been observed so strictly. The media attention on the campaign, both in Australia and internationally, helped fuel the growing opposition to apartheid, and laid the basis for even more confrontational actions, particularly the New Zealand anti-Springboks protests in 1981. Gary travelled to New Zealand to be part of these protests, and his eyes light up telling the story. “So there’s 25,0000 of us, and we’re marching around the perimeter of this rugby ground, and they’d set up this six-foot-high cyclone wire fence with barbed wire on top, all the way around. And so we were marching around, and all these rugby goers were standing up on the hill and yelling at us: ‘Go home you commo bastards! You’re weak as piss!’

“We must have been going around it on our second lap, when all of a sudden Rebecca Evans pulls out this megaphone and she says: ‘Operation Everest, Go!’ and then the front line of women suddenly turn and run as a group at the fence. We saw then that they were all wearing gloves. They just all leapt onto the top of the fence, and behind them a second line of women jumped onto the fence below them, forcing the fence down. As soon as these rugby supporters saw a flying wedge of women coming at them they scattered, and when they scattered they created a path onto the field, so 500 of us managed to get onto the field before the coppers closed the gap.”

Ultimately, it was not the international protests that dealt the decisive blow to the apartheid regime but the revolutionary uprising of black South African workers and youth. But international solidarity was important.

In the months and years following the fall of apartheid, world leaders who had been its open supporters or on the fence about it for years rushed to celebrate. Among these turncoats Gary includes Hawke, who, apart from being a “CIA stooge” and a “traitor to the union movement”, was a “hypocrite of the highest order” when it comes to pretending to have always been a passionate opponent of apartheid. Gary is also contemptuous of Nelson Mandela, as a “sell-out sucking up to the very people who called him a terrorist and a communist and supported his imprisonment”, a view Gary also very publicly expressed when Mandela visited Australia in 1990.

The most immediate and profound effect of the campaign against the Springboks in 1971 was the boost it gave to the Aboriginal rights movement, especially the struggle for land rights. Gary is clearly still moved thinking about this. “We were on a roll, and we argued to those joining the anti-apartheid movement that they needed to fight racism in their own backyard ... Paul Coe got up at one of the demonstrations and said: ‘You people need to start turning up at our land rights rallies or we will inevitably consider you hypocrites’. And to their credit, the leaders of the anti-apartheid movement accepted this challenge and began encouraging members of the movement to turn up to fight for Aboriginal rights.

“Our marches grew enormously as a result, and this gave us the momentum to set up the tent embassy ... The other thing that the anti-apartheid movement did was push Billy MacMahon, who was already a nervous, hapless, anxiety-ridden man, to become even more of a nervous wreck and to make a fatal political error by giving a speech on Invasion Day, 26 January 1972, about how he wasn’t going to do anything for Aboriginal rights. So out of this we said, ‘OK we will establish an embassy’. The embassy led to the single greatest breakthrough for Aboriginal rights, and the only time that any genuine land rights have ever been granted.”

When I ask him about what we might learn from this history that might be relevant to struggles today, Gary responds with optimism about the Black Lives Matter movement and the massive Invasion Day marches of recent years. “Those marches are pulling bigger crowds than we did. If 90,000 are prepared to come out on the streets for Invasion Day, that really shows that things can change, that we can start to shift consciousness.” But politics, as well as numbers, matters: “It can ironically be a hard thing to educate people about the nature of the boot that’s stomping on their neck but, what we need to do is get the 50 percent in Australia who are genuine about challenging racism ... and educate them as to the underlying cause, make them aware you can’t be anti-racist and pro-capitalist, it’s just a contradiction”.